More then just a meat market

Wherever you go in London the city appears to have layer upon layer of history – a rich tapestried embroidery of stories set over the millennia and before. Look up and the architecture describes decades and centuries of historical events while underneath the pavement beneath your feet lies evidence of long dead dynasties from the Viking, Roman, Medieval and Victorian pasts. You need not look too far to find seemingly modern sites that reveal a wealth of history and associated historical events .

Take Smith Market for example. It is an historic site which has been a cattle market for 865 years and which after the relocation of Billingsgate Fish market, Covent Garden and Spitalfields markets is still in charge of its own destiny today

As such it is a heritage site, and with so many historical important places being demolished in London today – ergo the London Wool and fruit exchange in Shoreditch – visitors and locals are urged to treasure its very existence.

Let’s get the standard wiki-type facts out of the way first. Smithfield is a locality in the ward of Farringdon Without situated at the City of London's northwest in central London, England. The principal street of the area is West Smithfield. A number of valued City institutions are located in the area, such as St Bartholomew's Hospital, the Charterhouse, and Livery Halls notably those of the Butchers' and Haberdashers' Companies, however Smithfield is best known for its ancient meat market, now well over a thousand years old and which is now London's only remaining wholesale market in continuous operation since medieval times.. It is a Grade II listed-covered market building and was designed by Victorian architect Sir Horace Jones in the second half of the 19th century. Some of its original market premises fell in to disuse in the late 20th century and faced the prospect of demolition. The Corporation of London's public enquiry in 2012 drew widespread support for an urban regeneration plan intent upon preserving Smithfield's historical identity and the old market survived again

In the beginning

Now for the really interesting stuff! Smithfield has borne witness to many bloody executions of heretics and political rebels over the centuries among many other religious reformers and dissenters the story of each one being enough to consume the average history buff for several days.

In 1174 the site was described by William Fitzstephen, clerk to Thomas à Becket (of will-someone rid-me-of-this troublesome-priest fame), as 'a smooth field where every Friday there is a celebrated rendezvous of fine horses to be sold, and in another quarter are placed vendibles of the peasant, swine with their deep flanks, and cows and oxen of immense bulk.' It is thought that the name Smithfield came from a corruption of ‘smeth field’ Saxon for 'Smoothfield'. The City of London gained market rights under a charter granted by Edward III in 1327. During these times Smithfield was a wide grassy space, just outside the northern wall of the City of London on the eastern bank of the River Fleet. Due to its access to grazing and water, it was used as London's principle livestock market. Meat has been bought and sold at Smithfield for more than 800 years. Some street names associated with the market are still in use, such as Cowcross Street, but many others, such as Duck Lane, Chick Street and Goose Alley, disappeared as the Victorians redeveloped the area.

Famous executions

In contrast to its trading heritage for many years Smithfield was the place where traitors were hung, drawn and quartered and perhaps the most famous victim was Sir William Wallace in 1305 for leading the his part in leading the revolting Scots against King Edward of England. Wallace, ensuring movie immortality by his portrayal by Mel Gibson a few years later, was tried in Westminster Hall (which today is part of the Palace of Westminster at the House of Commons entrance and close to the eastern end of the Abbey).

Wallaces’s sentence was read out immediately following the verdict, and included the full details of the punishment usually known as "hanging, drawing and quartering" that King Edward had introduced as the appropriate penalty for treason. He was then chained prostrate on a hurdle (just a piece of old fence really) and drawn by two horses through the filthy streets for the public to mock and stone (Edward Longshanks’ ironic idea of combining education with entertainment).

He was drawn first to the Tower of London (now in EC3) , about two and a half miles, and then on to Smithfield via Aldgate, another mile. He was hanged, but cut down while still breathing. While held upright by the hangman's rope, he had his privy parts cut away (all of them, and hence emasculation, not castration) and burned in the brazier in front of him. Then, still upright, his stomach was slit open so that he could be ritually disembowelled. His entrails were burnt on the brazier. If ever there was a lesson for erstwhile traitors here was a good one

In 1381, a short while after the Black Death had swept through Europe decimating over one third of the population, there was a shortage of people left to work the land. Recognising the power of ‘supply and demand’, the remaining peasants began to re-evaluate their worth and subsequently demanded higher wages and better working conditions. Led by Wat (Walter) Tyler the peasants of Kent formed a large mob and marched on the City of London via London Bride where they despatched over 200 locals suspected of being in cahoots with the King and his instruments of their suppression. One of these instruments, the Bishop of Southwark, was also beheaded and his head was mounted on the gate at London Bridge with his bishops mitre duly nailed on to denote office.

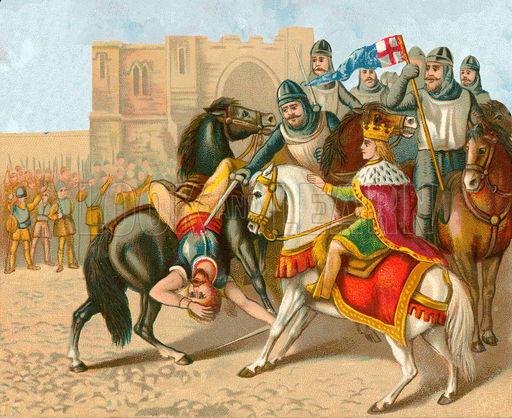

Not much is known of Wat Tyler with the exception of his fame as the leader of the English Peasant's Revolt of 1381. According to popular accounts, the commons of Kent after taking Rochester Castle, chose Wat Tyler of Maidstone as their captain. Under him they moved to Canterbury, Blackheath and London. After the peasants initial success, the king, Richard ll who had been cowering in the Tower of London emerged and called a peace parlay at Smithfield Market. The two sides met on horseback at Smithfield where blows were exchanged and William Walworth, mayor of London, wounded Wat with his sword. One of the king's squires then fell upon Wat and stabbed him in the stomach and he died (June 15, 1381). The revolt then duly petered out and after the remaining leaders were hunted down and butchered the peasants were left to return home unhindered. The episode could best be summed up as a nil-nil draw despite the huge numbers of casualties.

The first cattle market

In 1615, railings and sewers were provided in an attempt to bring order at a time when fighting and duelling were commonplace. Twenty-one years later, the Corporation of the City of London formally established a cattle market by means of a royal charter.

At the beginning of the 1700s complaints were made against unruly cattle and drunken herdsmen. Drovers, often the worse for drink, would have some fun by stampeding cattle on the way to market. The angry cattle would invade shops and houses, probably giving rise to the phrase 'like a bull in a china shop'. As the City of London expanded, so the need for meat grew and so did the market. By the middle of the 1700s, around 75,000 cattle and over 550,000 sheep were sold each year. A hundred years later, these numbers had increased to 220,000 cattle and 1.5 million sheep.

Dicken's Smithfield

Fast forward another hundred years or so and Smithfield is getting mentioned in the popular fiction of the day

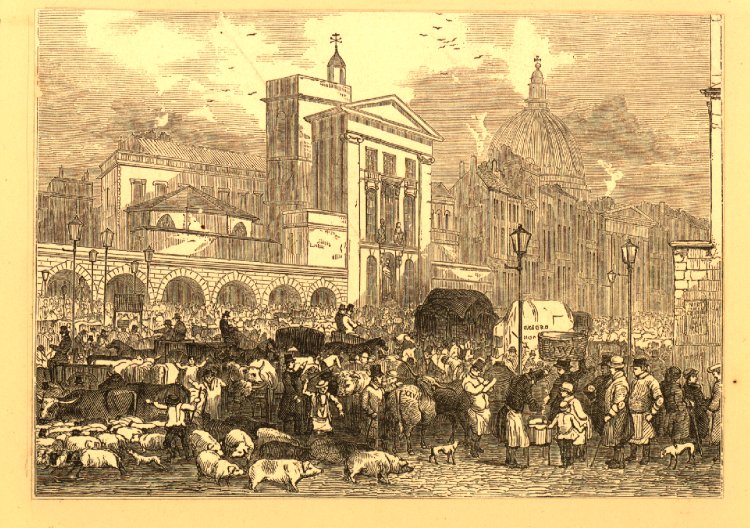

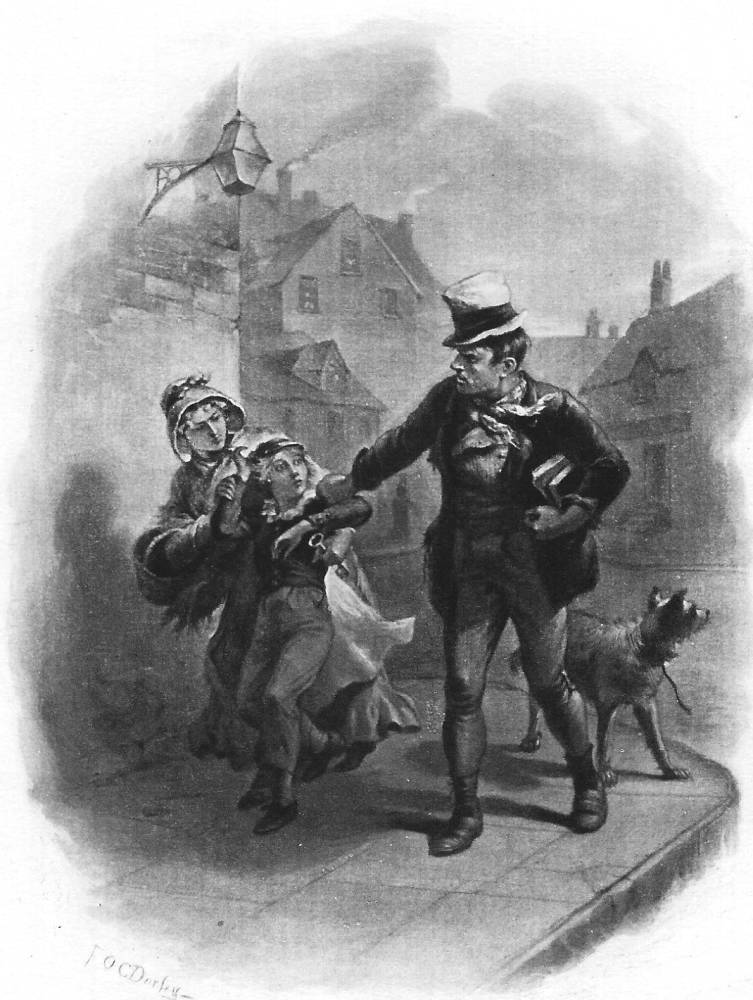

"Turning down Sun Street and Crown Street, and crossing Finsbury square, Mr. Sikes struck, by way of Chiswell Street, into Barbican: thence into Long Lane, and so into Smithfield; from which latter place arose a tumult of discordant sounds that filled Oliver Twist with amazement

….the ground was covered, nearly ankle deep, with filth and mire: A thick steam perpetually rising from the reeking bodies of the cattle."

So wrote Charles Dickens in Oliver Twist. He was referring to the Smithfield of the 1830s: with its :

"unwashed, unshaven, squalid and dirty figures ….a stunning and bewildering scene which quite confounded the senses".

These words from Dickens give a good idea of what Smithfield must have been like when it was still a 'live' meat market. It was not until 1855 that the 'live' market was moved further north in Islington to Copenhagen Fields. In 1868 the current building was opened as a 'dead' meat market which it remains today - as the last surviving historic wholesale market in central London. Smithfield's history has always been closely linked to that of Clerkenwell. Smithfield (Smooth field) and Clerkenwell (Clerk's Well) were two districts on the northern boundaries of the City of London. By the early 1850s, live cattle were still being driven to market to be slaughtered on site. The streets flowed with blood, as guts and entrails were dumped in such inadequate drainage channels that did exist – a scene that a writer of Dickens ability could do justice to so vividly.

The Wife Auctions

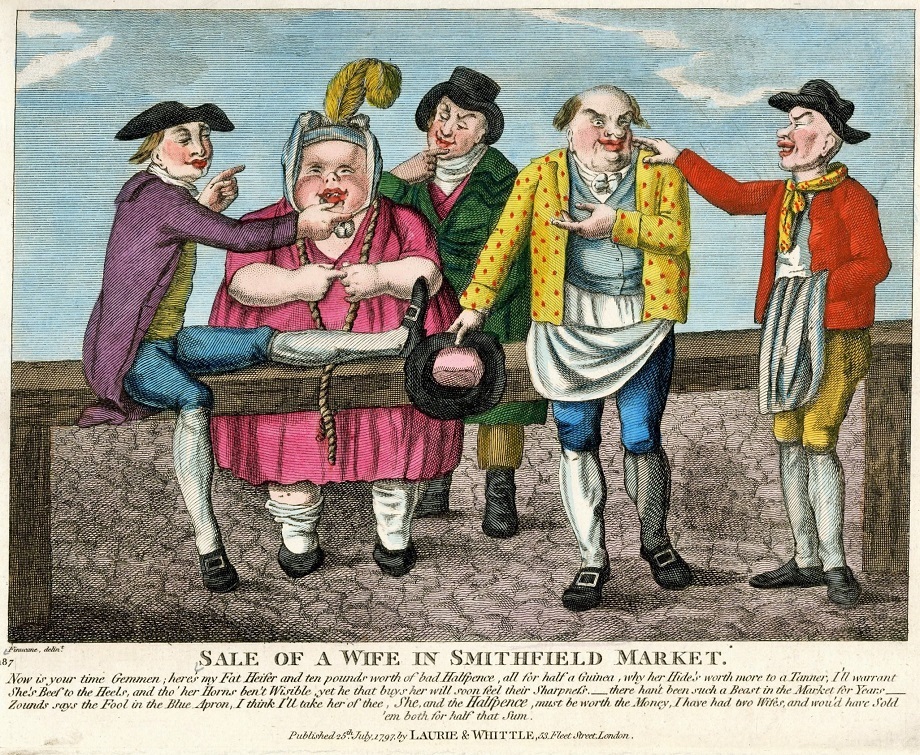

Away from Smithfield legacy of blood and gore, the market was also the site of another unenviable practice. Wife selling in England was a way of ending an unsatisfactory marriage by mutual agreement that probably began in the late 17th century, when divorce was a practical impossibility for all but the very wealthiest. Smithfield Market became a main point of exchange where these unhappy women could be desposed of by their heartless spouses. After parading his wife with a halter around her neck, arm, or waist, a husband would publicly auction her to the highest bidder. Although the custom had no basis in law and frequently resulted in prosecution, particularly from the mid-19th century onwards, the attitude of the authorities was equivocal.

Wife selling appears to have been widespread throughout England as depicted by the French caricature of Milord John Bull "booted and spurred, in Smithfield Market, crying 'à quinze livres ma femme!' [£15 for my wife], while Milady stood haltered in a pen".

Segway to the 21st century where the ancient market is a now thriving hub for the wholesale meat trade intertwined within a network of busy ‘quality’ restruants and noisy pubs. My favourite modern-day event here is the Christmas Meat Auction where attendees can make some great purchases in the style of a Dickensian Yuletide celebration. Just turn up at Harts’ establish on Christmas Eve to see what I am talking about. However whatever time of year you decide to visit Smithfield you can be assured of a plethora of historical fact (and fiction) lying just beneath the surface.

A brief history of Smithfield

A brief history of Smithfield

Load more triptoids

Load more triptoids